| Navtex |

ZCZC

W3EEE is contributing 'live' Navtex data as received on 518kHz in Pennsylvania to frisnit.com, a website in the UK, home of the 'Navtex Decoder' program described below. In addition to W3EEE an increasing number of other monitors are also contributing; the captured messages from 'elsewhere' make fascinating reading.

What is Navtex?

"Navtex" is an informational data broadcast system for shipping; anything from weather warnings, missing or overdue boats, ice warnings, and anything which may be considered a hazard to shipping.

The transmissions are from fairly powerful stations dotted around the coastline, with largely overlapping coverage. The main transmission frequency is 518kHz, just off the end of the AM broadcast band, with a secondary LF frequency of 490kHz less used and for 'local language' or secondary messages; Canadian stations for example use 490kHz for French. Additionally, there is an HF channel at 4209.5kHz. The signals themselves are 170Hz Frequency Shift Keying (FSK) centered on the nominal frequency (i.e. one carrier is 85Hz below, the other 85Hz above) and at a rate of 100 bps. Data is sent 'Forward Error Corrected' (FEC), which means the same characters are sent twice, one a few characters before its repeat, interleaved with subsequent data. Tuned in with a receiver set to SSB, it sounds like a high-speed 'burbling'.

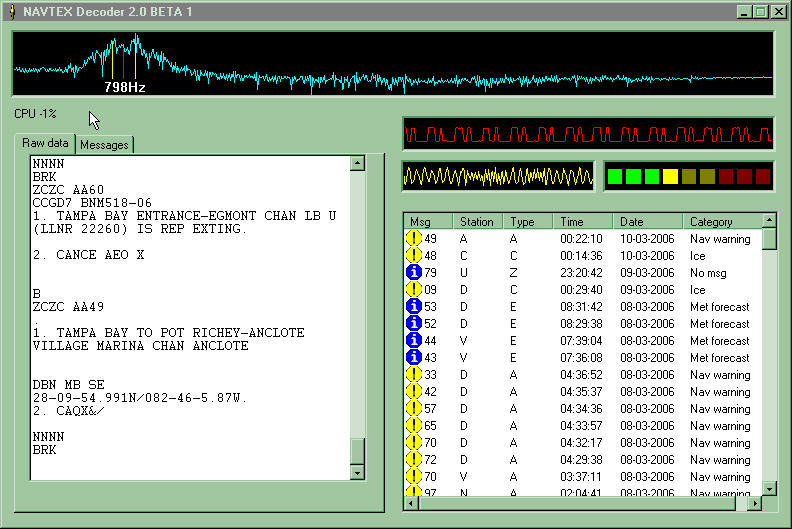

A full-size screen-shot of 'Navtex Decoder', a, um, Navtex decoder . . .

Why receive Navtex?

"Because It's There!". The information carried by the stations can vary from the useful (weather forecasts and such) through the interesting (ice warnings) to the downright harrowing (boats sunk or in distress). Also, the capture of data from as many of the different transmitters as possible, or from 'unusual' or distant stations is an interest in itself - in hobbyist world, this is called 'DXing' (DX is shorthand for 'Distance', but commonly means 'Rare').

Receiving Navtex.

Ships themselves have Navtex-specific receiving equipment; amateurs use a variety of means to receive and decode the signals. Although the system was conceived at a time of clattering mechanical teleprinters, nobody in their right mind does that now; computers are at the heart of today's systems.

A slightly old-fashioned way is using a hardware box called a Terminal Node Controller (TNC) or radio modem containing Navtex decoding hardware and firmware (example Kantronics 'KAM'), which feeds decoded ASCII plain text to a dumb display terminal, or a not-so-dumb 'puter running terminal emulation software (example Tera Term ). Many people swear by the sensitivity and accuracy of such hardware/firmware solutions with very weak signals.

By far the most common solution nowadays is to run software on a PC which decodes and often formats and organizes the resulting Navtex decodes. A receiver output is fed into the PC's soundcard input, which feeds the software. Different programs have different features, differing abilities to decode weak signals, and different costs (varying from the ever-popular 'free', to being part of a deluxe bijoux-and-bizarre-mode decoding suite costing hundreds of dollars). An excellent program with which to start is Navtex Decoder v2.0 , the beta version being free. SeaTTY ($35) is reportedly amongst the best for 'reading' weak signals.

Copying Navtex

Assumed here are a good SSB-capable receiver, an antenna capable of pulling in decent signals at ~500kHz, a computer with a soundcard, and a decode software program running on the PC. There's nothing difficult or extraordinary about the requirements; this should all be very familiar to anyone who's used a similar setup for PSK31, RTTY or other data modes.

First, find a Navtex signal. Anywhere near a coast, there should be a big loud Navtex signal, at least from time-to-time. Each station starts transmissions at programmed times, so there may be a wait until a 'local' one shows up. (Finding the schedule is detailed later, but random listening often scores.)

Propagation at 500kHz or so is such that during daytime only 'local' stations will be easily copiable (a few hundred miles or so). The target range for these stations is some 400 nautical miles. Night-time though, signals can carry thousands of miles, and reading Navtex messages from other continents is possible under good conditions.

Receiver Tuning

Tune the receiver in USB mode to 517kHz. Note: 517kHz, *not* the nominal frequency. In this way, a Navtex signal will be centered on 1kHz (the difference between 517 and 518) a perfect frequency to feed the 'puter's soundcard. Any such 'offset' frequency can be used provided it falls within the decoder's capability; the above plot was done with an 800Hz offset instead.

Receiver Filter

The optimum bandwidth of receiver filter is 500Hz (a wide 'CW' filter) - narrower than that the filter starts to modify the desired signal and copy possibly made worse, wider lets through unnecessary noise. However, Navtex signals are generally quite strong, so it is better to err on the side of wider rather than narrower. For all but real weak-signal 'DXing' of faraway stations, the normal SSB bandwidth of 2 - 3kHz is fine. Oh, yes: Turn all DSP de-noisers etc. off; DSP filters to narrow bandwidth are OK, but anything which auto-notches or noise-gates is bad ju-ju for data signals.

Computer Soundcard

Connect the 'Record' output from the receiver (only use the speaker or headphone output at a real push) to the soundcard's 'Line Input'. With a Navtex signal present from the receiver, ensure that the audio level is adequate for the decode program - they usually have a level indication of some sort. If the signal's missing, too low, or more unusually too loud, it may be necessary to open Windows' 'Volume Control' panel to fix this - Footnote [1] for details. It is recommended if possible to use the soundcard 'Line Input'; if not enough level to drive the program is available, try the 'Mic' input, though then there is the danger of overdriving the soundcard - a simple attenuator may be necessary in that case (Footnote [2]).

Ideally, and regardless of whether the 'Line' or 'Mic' input is used, an audio isolating transformer (to decouple the radio and computer grounds) should be used between the radio and 'puter (Footnote [3]). It will dramatically reduce hums, buzzes and other funny noises. That said, 'luck of the innocent' often applies, and the system can work without one.

The Decoding Program

Tuning with 'Navtex Decoder' |

Tuning with 'MultiPSK' |

Navtex Messages

A Navtex station's transmission can be short, just one message, or long - dozens of messages. The station can be on the air for seconds, or seemingly hours. Navtex messages themselves follow a distinct format; they may be short (a single line) or really long (pages) but they are always wrapped up in the same format, with a header and footer. Here's a short actual example:

ZCZC AA01

CCGD7 BNM 438-06

SAFETY BROADCAST ON VHF-FM UNTIL 260050Z FEB 06. FLORIDA - WEST

COAST - PINE ISLAND SOUND - HAZARD TO NAVIGATION - AT TIME 1950 LCL

24 FEB 06 THE CG HAS RECEIVED A REPORT OF A 20FL

FL-9625-GM PARTIALLY SUBMERGED WITH 2-3FT OF VSL STICKING OUT OF

WATER VSL IS ADRIFT IVO OF POSN 26-29.228 082-07.274W. ALL MARINERS

ARE REQUESTED TO EXERCISE CAUTION WHILE TRANSITING THE AREA.

NNNN

Yes, it's all upper-case: no, it's not shouting at you, it's just reflecting the teletype era in which the system was developed. 'ZCZC' is historically a 'beginning of message' header, whilst 'NNNN' denotes the end. Some stations insert 'BRK' between messages, but this isn't universal. The crucial part of a message (from a DXer's perspective, never mind any text about the QM2 taking out the Verrazano) is the identifying quartet - in this message 'AA01' (honestly, it really WAS message AA01 - I couldn't make that up!). The '01' is the message number; they seem to occur in random order; although likely issued in sequence, they probably expire or become irrelevant after different amounts of time. The second letter, 'A', indicates the type of message (A=Navigation warning, E=Meteorological, C=ice warning, J=GPS/DGPS notice etc. - See Footnote [4]). The all-important first letter, again 'A' in this instance, tells which station is doing the sending.

The world is carved up into several different Navtex Regions (East-coast US is in region IV - roman numerals for 4). Within each region are up to 26 stations, entitled unsurprisingly 'A' to 'Z'. So this message is from station 'A' in region IV (the region is guesswork, but since 'A' is in Miami and the next nearest 'A' station is thousands of miles away in France, it is a reasonable deduction). At this point a visit to Bill Hepburn's exceptional website will make a lot of this ID stuff clearer, and give you a firm idea of the stations you are likely to be able to receive and decode. Serious Navtex DXers tend to use a slightly more comprehensive notation amongst themselves to express reception of a station:

$04N

'$' says that this is a Navtex station, not an NDB, or a DGPS station reception.

'04' denotes the region, and, you guessed it

'N' is the station itself within that region.

So this would be Navtex station 'N' in section 'IV' - Chesapeake, VA, USA.

Guesswork truly begins when 'DXing' long-haul stations - clues such as message language and mentioned geographic features or place-names come into play to correctly identify the station, even if you have its 'letter' ID.

Lazy-man's DXing!

'DXing' carries the image of long, long days and nights, straining at every last whisper from a radio to capture the elusive rare stations . . . Well, Navtex DXing is a bit different. Basically, you set up the radio and 'puter, walk away and let it rip. Come back in a few hours, or the following morning, or after a long weekend and see what all that excruciating hard work has won you; the software will have decoded and saved all the messages it successfully captured from any stations it heard. Sweet! The first night I had 'Navtex Decoder' running, the following morning it had captured nearly all the mainland stations in section IV and most of the Caribbean; a notable - on the face of it - 'easy' omission being Bermuda. DXing in the fast lane, alright.

Ah, but then the fun starts. How about deliberately looking for a specific station? On Bill's site, each individual station's start-times are listed; as an example, section IV station 'A' (Miami, that captured above), reads as:

00, 04, 08, 12, 16, 2000

This means it starts on-the-hour (note the minutes on the last time given, 2000) every four hours. Times are GMT. (That's GMT. Don't argue with an ex-pat Brit.) So, in order to stand a chance of capturing the escapee Bermuda, I should be looking at:

00, 04, 08, 12, 16, 2010

That's ten minutes past the hour, every four-hour multiple. For mutual darkness to enhance propagation, this would mean 0010z, 0410z and 0810z.

Well, that's the theory, anyway. In practice stations often seem to start when they jolly well feel like it, or at least according to some Great Scheme to which we mortals aren't privy; additionally the bigger stations can drone on endlessly with a huge message queue blowing right past the neat little ten-minute time slot and several others that have the misfortune to follow. Obviously, trying to decode a distant station whilst your local is still trundling on is problematic. That is where advanced DXing techniques - in particular directional antennas to 'null out' the local - come into play. But that's another story.

Round-Up

Two prime resources for starting with Navtex are again:

Navtex Decoder v2.0 for a good and *free* decode program, and

Bill Hepburn's fabulous website.

LF hobbyists, who specialise in DXing and IDing NDB aero-beacons, DGPS transmitters and indeed these Navtex stations swap details of their conquests and receptions on a private reflector, 'NDBlist'. They are also a fund of knowledge and insight. Visit Alan Gale's excellent

'BeaconWorld' website, from which the reflector springs, and which is a wealth of LF-related information.

Addendum

So, as mentioned earlier, I laid plans for snagging the Bermuda Navtex station; instead, this showed up:

ZCZC BZ21

SUITE DIFFERENTS TEST LA STATION D ALGERRA_IO A LE PLAISIJ DE VOUS IN_O_MER Q_E SON

NQV_AX EST OPERA_ION_EL STOP TEST SATISFAIFANT AVEC LE TEBESSA ET LE BRIDES PRIERE

PASSER L_ POT EN 73 $3 )- 04_&4-..-589, $3 ,9543 '5-589, '74 =_54_ _

_+:_

: ?316

TEST CFC_FOR _LGER_DI

P

KNNNN

Which, standard flakey gibberish aside, was from a newly established and still testing station in Algeria. The 'B' designator is the same time-slot as Bermuda, but is from the '03' chain, around the Mediterranean, instead.

Good fun, this.

NNNN

Footnotes:

[1] Windows' 'Volume Control' panel can be found by clicking through //Start/Programs/Accesories/Entertainment/Volume Control//.

Usually, this program opens on the 'Playback' screen; to get to the required 'Recording' screen, click through //Options/Properties/Recording/OK//.

[2] To help prevent overload of a soundcard's 'Mic' input, an attenuator is useful. A suitable approximately 20dB 'L' attenuator consists of a 1kohm resistor across (in parallel with) the soundcard input, fed by a 10k resistor in series with the receiver output. These can fit within the connector at either end.

[3] Radio Shack sell small 600ohm/600ohm wire-ended transformers (273-1374) if you feel industrious enough to make your own isolator, or alternatively sell 'pregnant snakes' - a moulded cylindrical stereo transformer with phono leads attached - intended for fixing ground-loops in car-audio installations (270-054).

[4] Message Types (with thanks to Robert Connolly, GI7IVX). This is the second letter in the message identifying quartet:

[5] There is no number five. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!

© Steve Dove, W3EEE, 2006