| One Man and his WOD |

One Man and his WOD

Back in the mists of time, or at least the mid-sixties, lived a spotty-faced herbert in Oxfordshire, in whom his Dad had sown the seeds of a radio-based existence. (Upon catching his first glimpse of waveguide towards the end of the war, the Dad had wisely eschewed radar research for a life in hospital management.) On his heaps of clapped-out old valve radios, the Spotty kept tripping across this repetitive thing that sounded like Morse code; it was loud, too. Louder than Caroline, or even Radio London (*1) for that matter. Not as loud as the BBC Third Programme from Daventry, but then nothing was. Sly old thing that he was, the Dad just answered "Well, find out everything you can about it..." in answer to the inevitable question.

Firstly. What did the Morse mean? Find copy of a boy- scout manual with the code in and painstakingly translate "dot-dash-dash, dash-dash-dash, dash-dot-dot" into "WOD".

WOD? What the snot is a WOD?

Secondly. Wavelength. Correlate and average indications from all aforementioned ancient wirelesses. Looks like about 416m. Frequency? Eh? It repeats about every ten seconds. No? Then what? (Brief tutorial from the Dad, replete with sinusoidally waving arms, followed by deposition of a heap of dusty tomes stamped "Ministry Of War - Secret" in Spotty's lap. Reassurance that they were in fact just radio textbooks and that there was little likelyhood that Spotty was about to be nicked under the Official Secrets Act. Slide rule. Figure out relationship between wavelength and frequency... so 416m is, uh, about 721kc/s (yes, Virginia, KiloCycles). Trip across a list of medium-wave broadcasters in kc/s instead of metres. They're all 9kc/s (nine?) apart. And 721 ain't one of them. Hmm.

Thirdly. Location. There's nothing on that list of stations called "WOD" or anything like. But it's loud. Must be fairly near if it doesn't warrant 'national' attention. No documentation on it; no-one Spotty knew had a clue; no-one's Dad had a clue, except Spotty's, and he wasn't saying. Stumped.

Until an epiphany in the living room a couple of weeks later. Moving the Mum's prized new table-top transistor radio across the room to better get 'Big-L' (*2), Spotty noticed as he turned around the signal dropped out. Fearful of having broken the new household toy, back it went up on the sideboard, where it continued to work happily. Wait a minute. Picks it up, turns it, Big-L turns into No-L then comes back up. Same on "The Sound Of The Nation" (*3); and on 390 (*4). But the BBC Light Programme doesn't - oh, yes it does, but with the radio turned slightly differently. Eh? BBC Third Programme; different again... that WOD thing, different yet. Radio out in the garden where he can hear clearer; yep, same thing, signals drop out from all kinds of different angles. "D-a-a-a-a-d?"

"Read Chapter Eight of Scroggie" was all the help forthcoming. Scroggie was still in the most part impenetrable squiggles and maths, but the drawings kind of made sense, and here was one of a 'loop aerial', and a figure-of-8 pattern drawn around it. OK, so this thing works well off the ends, and badly off the sides. So badly they call it 'null'. Why on earth would anyone want an aerial that deliberately works badly?

G O N G !

"The ferrite-rod antenna in your Mum's radio is just a modern scaled-down loop antenna". The most clue the Dad had given so far. It probably hurt him.

Back out to the garden with the Mum's radio and an atlas open at southern England. Let's see, the garden runs sort-of east/west. Well, that makes sense; the pirates go quiet in line with the garden and they're in the Thames Estuary some 80 miles east-ish; Daventry is quietest north-ish, yep, that jives. Hey this is (insert whatever word meant "COOL!" back then; probably "FAB!"). Now, where's WOD. Between NW/SE and N/S (that's NNW/SSE, right?). That means it's somewhere on a line through Oxford and east of Reading.

In one of the less professional-looking books the Dad had bestowed upon him (in fact it looked like a badly-bound collection of badly-typed and badly-mimeographed pages on really bad paper, which is precisely what wartime manuals often were) and exceeding Scroggie in impenetrability the Spotty remembered and re-found a discussion of 'huff-duff' and the need for at least two 'stations' for 'triangulation'. And these 'stations' should ideally form an equilateral triangle with the rogue station. OK, understood. But, wait - don't have another station... this one could move though, right? But equilateral, that means to be meaningful it's got to travel (travel means 'bike') as far away as WOD probably is, either, uh, yes, east or west. That means bike this radio Goring-on-Thames way or Henley-on-Thames way, just for starters. Umm. In his reverie it dawns on Spotty that he goes to school in Henley; a nearly pain-free second 'triangulation station'.

'Nearly' being the operative word. The next, highly technical part: How to smuggle the Mum's table-radio out of the house, onto the school bus and into school without incurring certain death or a probable detention respectively. Or both. Second part easier than the first; Spotty explained to Ian Mulelly the Physics Master what he was up to; he understood! He was encouraging! Turns out he'd heard WOD also and casually wondered what it was, too! Great chap, even if he did end up marrying that German exchange student teacher. She was a cracker, though. Got the official OK and a chitty from him. As for the home end... there must be a God! That night the Mum gathers all for one of those serious family "who- broke-the-garden-shed-window" kind of talks, only she sombrely explained that she wouldn't be around for the next few days, since she's working as duty nurse on a nearby film-shoot, and they work mostly at night (even the daylight scenes apparently, quite bizarre...). "So can you look after yourselves for a bit? - No Parties!" - shot like a cannon at Spotty's very sixties elder brother.

A defining moment in Spotty's existence; a 'nerd' forever more in his own eyes and others'; as he clambered onto the school bus the following morning with the smuggled radio; as he did his bearing-finding dance over the atlas on the school lawn. as he shouted aloud "Woodley!" as two pencil-lines collided in a smudge on the map...

The Hunt is On

Spotty and his buddy Dave heaved and puffed on their bikes down through the Chiltern hills and over the Thames at Sonning that Saturday. Dave, bemused, was nevertheless up for an adventure however obscure it's reason; and anyway he was entertained by 'Kenny and Cash' (*5) coming from the table-radio perilously bungee'd onto Spotty's handlebars. ("Scratch, Mum? What scratch?")

Woodley then was still a village of it's own somewhat east of Reading. Growing, and with a cluster of light industrial factories sprouting on and around what used to be Woodley Aerodrome. Unlikely any plane had landed there since the war, it was like many an old military base in Britain at the time; a broad, flat island of overgrown greenery and decaying shabby huts being pressed on all sides by a burgeoning suburbia. It'd only been, what, twenty years since the war and probably the government was still hedging it's bets, only unloading what properties it had to, or more likely cannily waiting for the land-value to sky-rocket. Some of the old lean-tos and Quonset huts still had small outfits working in them, some had just crumbled. Where youngsters once rolled and rotated aeroplanes in earnest, now they did so in cars: learn in them, drive them way too fast once learnt in, and park in them with suitably steamy company. The control tower, perhaps the only well-built building, looked mournfully boarded-up and padlocked. Woodley Aerodrome's biggest claim to fame is that it's where Douglas Bader (*6) "pranged his jolly old kite, what?" and lost both his legs.

Spotty and Dave's bearings taken en route all seemed to point there. But once there... WOD seemed to come from everywhere; it was so loud, it was impossible to find a 'null' at all. Oh, well. Old military bases were always fun to explore; there were plenty around where they lived; refugee camps, D-Day build-up camps (Canadians mostly), couple of real good fighter 'dromes. RAF Benson was still operational, home of wartime photo-reconaissance and latterly of the Queen's Flight, and a great air-show once in a while (intentional or not). (Ever see a 'Vulcan' nuke-bomber turn on end and fly straight up? More to the point, did you ever FEEL it? Woah, Man . . .)

They'd pretty much decided to call it a day after slogging all the way around the periphery road. they didn't even know what they were looking for, really; Spotty's notion of what a radio transmitter site looked like was based on the Dad pointing out BBC Crystal Palace in London and the experimental radar station he'd worked at for a while near Swanage; both these were Eiffel- Tower shaped, steel, lattice and awesomely tall. Spotty could only imagine that something as loud as WOD _must_ be coming from something like that. So when Dave pointed up a gravel track off the periphery road to a couple of brown sticks poking out over the top of a row of pine trees, a brutal clash of images was brewing. The tattered, bent and peeling 'MOD-WARNING - All Trespassers Will Be Disembowelled' (or such) sign on a rusty chicken- wire fence gave them their first clue.

On a small plot, maybe 150' by 50' were two telegraph poles some 50 feet high and 100 feet apart, and a little wooden hut between. Wires made a 'T' between the poles, the tail running down to an insulator with what looked for the world like an up-turned mixing bowl dangling on the wire above it. The radio was receiving WOD really well; nothing else mind you, just WOD, all over the dial.

This was, IT?

No teams of earnest looking men in white coats with slide-rules tending over endless serried racks of gleaming incomprehensible machinery?

A wooden shed?

After the reality had had chance to settle in and make itself comfortable, the emotions changed.

This was IT!

The romance with 'phone poles and huts had begun. Actually, with anything that radiates at all...

Fast Forward

Woodley is an indistinct suburb of Reading nowadays. What was Woodley Aerodrome is covered with characterless council and middle-income housing estates. The Dad ended up living there, oddly enough. The streets have names like "Hurricane Way", "Spitfire Street", "Bader Road"; the control tower is still there - it went through something of a renaissance as a dodgy night-club.

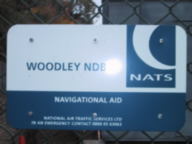

WOD is still there, too.

It turned out that WOD was actually on 723.5kc/s - 'twixt two of the 9kc/s spaced broadcast channels so as to minimise interference. It 'got out' like a rocket. As NDBs go (Non-Directional Beacons, as Spotty later discovered) WOD was a pretty important and well-known one amongst aviators (for whom they exist). It is in line with the main 09/27 L & R runways at Heathrow some 20 miles east and as such used as a 'marker' - a point of reference. In the mid-70s as the broadcast bands were wrested from solely BBC to become commercial-prevalent (mainly a legacy of those pirates, bless'em) WOD was booted off medium-wave and into the 'normal' NDB band, landing on 352kHz. They took down the shed, dumping a modern pre-fab equipment trailer in it's place. The telegraph poles and their 'T' antenna were replaced by a skinny white fibreglass stick with little curly- cue anti-corona top-loading.

Yet more recently, another refit; a self-suppoting lattice tower graced with a 'top-hat' for greater efficiency, and yet a different hut. Oh, and a new sign, not peeling.

It isn't Spotty's WOD, but it's still WOD.

Some technical notes . . .

T1154 (top), R1155. (See VK2BV's website.) |

The repetitive identifier keying was done by an excruciatingly Heath Robinson (US translation: Rube Goldberg) contraption of a motor-driven rotating disk, either with pegs in around the edge, or notches in the periphery, which activated an adjacent switch to key the transmitter. Naturally, this was prone to the occasional failure, and Spotty remembers many occasions when 'WOD' got stuck on, or twitched helplessly until someone legged it out to Woodley to fix it. It was likely normal for there to be redundant transmitter / keyer setups: the clue behind this is the time two out-of-sync keyers were heard hammering away through two transmitters beating against each other, providing a good day's entertainment. That the transmitters could stand being accidentally fed into each other for hours was a testament to the ruggedness of those old sets. Try that today, sunbeam . . .

* Footnotes to the above story:

(*1) Radio Caroline and Radio London were the two most powerful and popular of the mid-sixties pirate radio stations off the coast of the UK. Amazing as it seems now, these 'pirates' had a bigger market share than the then three BBC services put together. No wonder they were eventually legislated out of existence. BBC Radio One, which belatedly sprang from the ashes, was a thinly disguised 'Radio London'.

(*2) 'Big-L', Radio London.

(*3) "The Sound of the Nation" - Radio Caroline.

(*4) 390, Radio 390 (on 390 metres). A pirate that inhabited a wartime anti-aircraft gun platform out in international waters. The government coughed, artfully redrew some maps and declared that the waters weren't quite international enough, and so forced the station to close. It had a terrific signal; its programming was 'easy listening', which attracted a large - and more mainstream - audience that most of the top-40 pirates had ignored.

(*5) 'Kenny and Cash' - a ground-breaking and highly popular two-DJ morning show on Radio London (and latterly on the land-based commercial Capital Radio). Kenny Everett, after a phase of sufficient anti-establishmentism to keep him off the air, went on to be enormously successful on TV and is widely regarded as one of Britain's finest comedians, in the same league as the 'Pythons'. He died of AIDS in 1995. Dave Cash is still a pillar of UK radio.

(*6) Douglas Bader became a national hero, as personification of the "RAF spirit" that won the Battle of Britain. At Woodley Aerodrome in 1931 he was playing silly-buggers showing off acrobatically when he drove his Bristol Bulldog into the grass doing a low-level roll. He lost both his legs, somewhat disadvantageous for a fighter pilot. Come wartime, though, he blagged his way back into the RAF, became an 'ace', and eventually a Wing Commander, latterly becoming involved arguably on the wrong side of an ugly political imbroglio (Leigh-Mallory vs. Keith Park), and spending much of the war languishing in Colditz.

© Steve Dove, W3EEE, 1996, 2004,5